Have You Been Continuously Unemployed for the Last 27 Weeks Since at Least 08 16 2017

Labour Force Survey, January 2022

Released: 2022-02-04

- Tab 1

- Tab 2

Employment — Canada

19,176,000

January 2022

-1.0%

(monthly change)

Unemployment rate — Canada

6.5%

January 2022

0.5 pts

(monthly change)

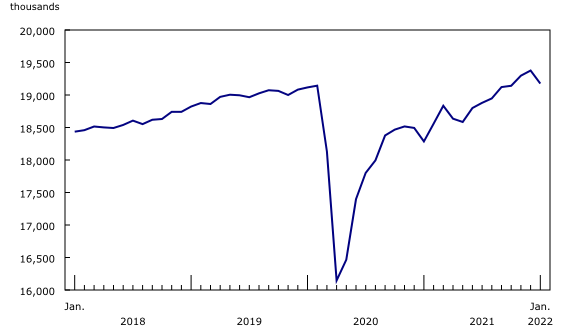

Employment fell by 200,000 (-1.0%) in January and the unemployment rate rose 0.5 percentage points to 6.5%.

With the spread of the Omicron variant of COVID-19, many jurisdictions had implemented stricter public health measures by the Labour Force Survey (LFS) reference week of January 9 to 15. Capacity limits or closures had been re-introduced in retail stores and high-contact settings such as restaurants, bars, concert halls and gyms. Also, schools in several jurisdictions had switched to online learning.

January employment declines were driven by Ontario and Quebec, and accommodation and food services was the hardest-hit industry. Youth and core-aged women, who are more likely than other demographic groups to work in industries affected by the public health measures in place in January, saw the largest impacts.

The number of people who were employed but worked less than half their usual hours rose by 620,000 (+66.1%) in January, the largest increase since March 2020. Total hours worked fell 2.2% after being at pre-COVID levels in November and December 2021.

Chart 1

Employment dips amidst tightening of public health measures

Highlights

Employment declines in January during the fifth wave of the pandemic

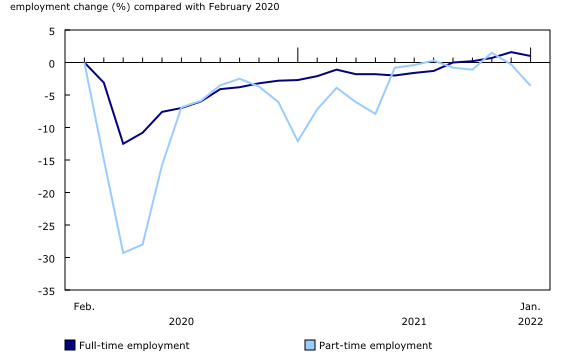

Employment fell by 200,000 (-1.0%) in January, spread across both part-time (-117,000; -3.3%) and full-time (-83,000; -0.5%) work.

Total hours worked fell 2.2% after being at pre-COVID levels in November and December 2021.

The number of employed people who worked less than half their usual hours rose by 620,000 (+66.1%) in January 2022, the largest increase since March 2020.

Youth saw declines in both part-time (-93,000; -7.1%) and full-time (-46,000; -3.5%) work.

Employment fell among women in the core working ages of 25 to 54, entirely in part-time work (-43,000; -4.3%).

All of the employment decline in January 2022 was among private sector employees (-206,000; -1.6%).

In January, 1 in 10 (10.0%) employees were absent from their job due to illness or disability.

Almost one-quarter of workers (24.3%) reported that they usually work exclusively at home.

Average hourly wages grew 2.4% (+$0.72) on a year-over-year basis in January, down from 2.7% in November and December 2021.

Employment in services-producing industries fell by 223,000. Accommodation and food services (-113,000), information, culture and recreation (-48,000) and retail trade (-26,000) saw the largest declines.

Employment increased by 23,000 in the goods-producing sector.

Employment declined in Ontario, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island.

Unemployment rate increases for the first time in nine months

The unemployment rate increased 0.5 percentage points to 6.5% in January, the first increase since April 2021.

The total number of unemployed people increased by 106,000 (+8.6%) to 1.34 million.

The number of people on temporary lay-off or scheduled to start a job in the near future rose by 120,000 (+130.5%).

The unemployment rate for youth aged 15 to 24 rose 2.5 percentage points to 13.6%.

Women aged 25 to 54 also saw an increase in their unemployment rate (+0.6 percentage points to 5.3%).

The labour force participation rate among the population aged 15 years and older fell 0.4 percentage points to 65.0% in January.

Drop in employment mostly among youth and core-aged women

As during previous waves of the pandemic, youth aged 15 to 24 were most affected by employment losses in January, reflecting the fact that they are more likely to work in industries directly affected by COVID-19 public health measures. Youth saw notable declines in both part-time (-93,000; -7.1%) and full-time (-46,000; -3.5%) work. Employment declines were similar for teenagers (aged 15 to 19) and for youth in their early 20s (aged 20 to 24), as well as for both young men and young women.

Employment also fell among women in the core working ages of 25 to 54 in January, entirely in part-time work (-43,000; -4.3%). Among core-aged men, both full-time and part-time employment held steady. For core-aged people identifying as belonging to groups designated as visible minorities, the employment rate declined by a similar amount in January (-1.6 percentage points to 79.8%) as for those who are not a visible minority and not Indigenous (-1.5 percentage points to 84.6%) (not seasonally adjusted).

There was no change in total employment for men or women aged 55 and older in January.

Chart 2

As in January 2021, youth and core-aged women most affected by employment losses in January 2022

Employment rate remains above its pre-COVID level among Indigenous youth

The employment decline among youth in January brought their overall employment rate down 3.2 percentage points to 55.4%.

While the employment rate among non-Indigenous youth returned to its January 2020 level (54.7%), the employment rate for Indigenous youth remained 4.3 percentage points above its January 2020 level at 52.7%. The gap in the employment rate between the two groups had narrowed during the fall of 2021 (three-month moving averages, not seasonally adjusted).

LFS information for Indigenous peoples reflects the experience of those who identify as First Nations people living off reserve, Métis, and Inuit, in the provinces.

Employment decline entirely among private sector employees

All of the employment decline in January was among private sector employees (-206,000; -1.6%), reflecting large losses in the accommodation and food services; and information, culture and recreation industries. Following the decline, the number of employees in the private sector was essentially the same as in February 2020.

The number of public sector employees held steady in January and remained above its pre-pandemic February 2020 level (+305,000; +7.8%). Self-employment was little changed in January, the sixth consecutive month with no growth, and remained 7.9% (-227,000) below its February 2020 level.

Losses in both full-time and part-time work

Employment declines in January were spread across both part-time (-117,000; -3.3%) and full-time (-83,000; -0.5%) work. Part-time employment fell below its pre-pandemic level after having recovered at the end of 2021, while full-time employment remained higher than in February 2020.

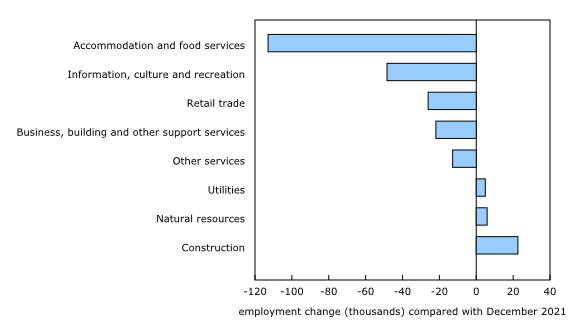

Chart 3

Part-time employment falls below its pre-pandemic level

Year-over-year wage growth holds steady

Average hourly wages grew 2.4% (+$0.72) on a year-over-year basis in January, down from 2.7% in November and December 2021 (not seasonally adjusted). The January 2022 year-over-year change was similar to the average annual wage growth of 2.5% observed in the five years from 2015 to 2019.

The concentration of January 2022 employment losses in lower-wage industries did not have a significant impact on year-over-year wage change, partly because employment in these industries experienced similar losses in January 2021 as a result of the third wave of COVID-19.

Record-high share of employees misses work due to illness or disability

Absences from work due to illness or disability—that is, for any short or long term health-related reason—tend to follow a seasonal pattern, and typically peak in the winter. However, as the Omicron variant of COVID-19 spread across the country, absences due to illness or disability reached record highs in January.

Specifically, 1 in 10 (10.0%) employees were absent from their job for all or part of the January reference week due to illness or disability, approximately one-third higher than the average observed in the month of January from 2017 to 2019 (7.3%). Prior to January 2022, the highest level of absences due to illness or disability was 8.1% in March 2020, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (not seasonally adjusted).

Absences due to illness and disability exceeded typical January levels by 5.6 percentage points in accommodation and food services (10.2%), and by 5.4 percentage points in retail trade (11.7%), two industries where a large proportion of jobs require close proximity to others. In the health care and social assistance industry, which typically has one of the highest proportions of employees absent due to illness and disability, absences in January 2022 (13.3%) exceeded the January 2017-to-2019 average by 3.4 percentage points (not seasonally adjusted).

Almost all other industries had higher-than-average absences due to illness or disability in January 2022, with the exception of the educational services, public administration, and utilities industries, where absences were slightly below typical levels. Schools in most jurisdictions were providing online learning during the January 2022 reference week.

Infographic 1

Almost all industries had higher-than-average absences due to illness or disability in January

The proportion of employees absent due to illness or disability was higher than the typical January level among both men (+3.1 percentage points to 9.4%) and women (+2.3 percentage points to 10.7%). Among all age groups, youth aged 15 to 24 had the highest increase (+6.9 percentage points to 11.8%).

Among Canada's largest visible minority groups, Filipino Canadians—who are more likely to work in health care and social assistance—were most likely to be absent from work due to illness or disability in January 2022 (13.1%). The proportion among South Asian (9.3%) and Black (10.5%) Canadians was closer to that seen among people who are not a visible minority and not Indigenous (9.9%), while it was lower among Chinese Canadians (7.0%).

Across provinces, the percentage of employees absent from work in the January reference week due to illness or disability ranged from 7.8% in Prince Edward Island to 12.0% in Saskatchewan and British Columbia. The proportion in Prince Edward Island was on par with typical January levels, while it was more than 4 percentage points higher than a typical January in both Saskatchewan and British Columbia.

Working from home increases in response to Omicron public health measures

During the LFS reference week of January 9 to 15, several provinces, including Ontario and Quebec, had implemented stringent public health measures and had encouraged employers to facilitate working from home wherever possible. Of all those who worked during the LFS reference week, more than 4 in 10 (43.0%) worked most of their hours from home. Among those who do not usually work any of their hours at home, 30.3% worked at home for at least part of the week. Industries where a larger proportion of workers do not usually work from home but where many did so during the reference week included educational services, construction and health care and social assistance (not seasonally adjusted).

For one-quarter of Canadians, working from home has become a long-term way of working

For many Canadians, the shift to working from home has been one of the most significant effects of COVID-19. For some, this has been a series of short-term adaptations in response to the tightening and easing of public health restrictions, as in January 2022. For others, it has been an ongoing reality since March 2020.

To shed additional light on the evolution of working from home, January LFS respondents were asked to report where they usually work at the present time. While the majority of workers (72.1%) reported they usually work only at locations other than home, almost one-quarter (24.3%) reported that, at the present time, they usually work exclusively at home. In comparison, the 2016 Census of Population reported that 7.5% of workers usually worked at home.

In January, the share of workers who usually work exclusively at home was higher in urban areas (25.6%) than in rural areas (17.2%). The Ottawa–Gatineau (40.0%) and Toronto (34.7%) census metropolitan areas (CMAs) had among the highest proportions of workers who only worked from home, while Saskatoon (10.4%) and Abbotsford–Mission (12.2%) had among the lowest shares of home-based workers (population aged 15 to 69; not seasonally adjusted).

To take advantage of the benefits offered by working from home, many employers and self-employed workers have begun to implement 'hybrid' ways of working, with some days worked at home and others at the office or at a work site. As of January, fewer than 1 in 20 (664,000; 3.6%) workers reported being in such 'hybrid' arrangements, with the highest proportion being among workers in professional, scientific and technical services (7.1%) and in finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing (7.0%) (population aged 15 to 69; not seasonally adjusted).

Unemployment rate increases for the first time in nine months

The unemployment rate was 6.5% in January, up 0.5 percentage points from December 2021. This was the first increase since the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2021.

The total number of unemployed people increased by 106,000 (+8.6%) to 1.34 million in January 2022 and was 184,000 (+15.9%) higher than in February 2020. The adjusted unemployment rate—which includes people who wanted a job but did not look for one—was 8.5% in January 2022.

The increase in unemployment in January was entirely due to more people on temporary lay-off or scheduled to start a job in the near future (+120,000; +130.5%), while the number of people looking for work was little changed.

Chart 4

Unemployment rate rises for the first time since April 2021

Unemployment rate rises among youth and core-aged women

The unemployment rate for youth aged 15 to 24 rose 2.5 percentage points to 13.6% in January. Increases were seen among both young men (+2.7 percentage points to 14.9%) and young women (+2.3 percentage points to 12.3%).

Women in the core working age group of 25 to 54 also saw an increase in their unemployment rate (+0.6 percentage points to 5.3%), while the rates among core-aged men (4.8%) and people aged 55 and older (6.4%) were little changed.

One in five long-term unemployed exit labour force in January

The number of people who had been continuously unemployed for 27 weeks or more fell for the third consecutive month in January, down 36,000 (-12.2%) to 263,000. Long-term unemployment as a proportion of total unemployment was down 4.6 percentage points to 19.6%, but remained above the pre-pandemic February 2020 proportion of 15.6%.

The decrease in long-term unemployment was primarily due to a rise in the proportion of the long-term unemployed who stopped looking for work. Among people who were long-term unemployed in December 2021, one in five (20.0%) left the labour force in January 2022, higher than the average rate (14.2%) observed over the previous six months. In January, the majority of the long-term unemployed (68.7%) remained unemployed, while 11.3% entered into employment.

Absences fuel an increase in labour underutilization

The labour underutilization rate—the proportion of people in the potential labour force who are unemployed; want a job but have not looked for one; or are employed but working less than half of their usual hours—rose 3.7 percentage points to 15.9% in January.

The number of people working less than half their usual hours rose by 620,000 (+66.1%) in January, consistent with an increase in absences due to a personal illness or disability. The number of people who wanted a job but did not look for one also increased in January, rising by 46,000 (+11.9%).

Labour force participation drops the most among youth

As seen during previous waves of the pandemic, the labour force participation rate—that is, the share of the population aged 15 and older who are either employed or unemployed—dipped in January, down 0.4 percentage points to 65.0%.

The largest decline was among young women aged 15 to 24 (-2.1 percentage points to 65.1%), followed by young men (-1.4 percentage points to 63.3%).

The participation rate among people in the core working age group was 88.2% in January, 0.2 percentage points below the all-time high recorded in December 2021. The rate ticked down for both men (-0.2 percentage points to 91.9%) and women (-0.3 percentage points to 84.4%) in this age group.

The participation rate for men aged 55 and older decreased by 0.4 percentage points to 42.3% in January, while the rate was little changed for women in the same age group (31.4%).

First employment decline in the services-producing sector since April 2021

The number of people working in services-producing industries fell by 223,000 in January 2022. With this decline, employment in the sector returned to its pre-pandemic February 2020 level after having surpassed its pre-pandemic level in September.

Consistent with public health measures introduced in several provinces to limit the spread of the Omicron variant, there were notable employment declines in accommodation and food services (-113,000), information, culture and recreation (-48,000) and retail trade (-26,000) in January. Employment also fell in business, building and other support services (-22,000) and in "other" services (-13,000).

In contrast, employment increased by 23,000 in the goods-producing sector, building on the gain of 43,000 recorded in December 2021. The increase in January 2022 was driven by the construction industry (+23,000), with natural resources (+5,900) also contributing to the increase.

Chart 5

Notable employment losses in accommodation and food services and information, culture and recreation in January

Largest employment decline in accommodation and food services since the first wave of the pandemic

Employment fell by 113,000 (-11.1%) in accommodation and food services in January, the largest monthly decline in the industry since April 2020. In many provinces, businesses in accommodation and food services faced public health restrictions during the LFS reference week. In Ontario and Quebec, which account for nearly all of the employment decline in accommodation and food services, a ban on indoor dining was in effect. Nationally, employment in the industry fell to 26.4% (-324,000) below its pre-COVID February 2020 level.

Employment in information, culture and recreation loses gains made in recent months

The number of people working in information, culture and recreation fell by 48,000 (-6.2%) in January, almost entirely as a result of losses in Ontario. Indoor venues such as theatres and cinemas, as well as sports and recreation facilities were closed in the province during most of January. Nationally, a notable employment decline was recorded among youth aged 15 to 24 (-25,000, not seasonally adjusted).

The January loss—the largest since the first wave of the pandemic in 2020—brought employment in information, culture and recreation back down to the level recorded in August 2021. There were 5.3% (-42,000) fewer people working in the industry in January 2022 than in February 2020.

Retail trade employment declines to pre-pandemic level

In retail trade, where store capacity limits introduced in several provinces in mid-December 2021 remained in place during the January 2022 LFS reference week, employment fell by 26,000 (-1.1%) in January, with most of the losses concentrated among youth. The monthly decline brought the number of people working in the industry back down to its pre-COVID February 2020 level.

Employment rises for a second consecutive month in construction

Employment rose by 23,000 (+1.5%) in construction in January 2022, almost entirely as a result of gains in Ontario. The national-level increase adds to a gain of 35,000 recorded in December 2021. Employment gains in construction over the last two months follow an acceleration in economic activity in the industry during the fall, with investment in building construction growing in both October and November.

Employment down in five provinces

Employment dropped by 146,000 (-1.9%) in Ontario in January. Among all other provinces, Prince Edward Island posted the largest proportional decrease (-3.5%; -2,900), followed by Newfoundland and Labrador (-1.7%; -3,900), Quebec (-1.4%; -63,000) and New Brunswick (-0.9%; -3,100). In contrast, the number of people working in Saskatchewan (+0.7%; +3,900) increased. There was little change in Alberta, British Columbia, Nova Scotia and Manitoba.

For further information on key province and industry level labour market indicators, see "Labour Force Survey in brief: Interactive app."

The employment decline in Ontario (-146,000; -1.9%) followed seven consecutive monthly gains totalling 433,000 (+6.1%). Losses in January were predominantly in part-time work and among youth aged 15 to 24 and women aged 25 to 54. Industries most affected were accommodation and food services, followed by information, culture and recreation. The unemployment rate increased 1.2 percentage points to 7.3%.

Employment in the Toronto CMA dropped by 108,000 (-3.0%) in January 2022, similar to the cumulative two-month decline in December 2020 and January 2021 when the CMA was also under tight public health measures. The unemployment rate in the CMA rose to 8.8% (+1.9 percentage points) in January 2022.

In Prince Edward Island, employment fell by 2,900 (-3.5%) in January, coinciding with new capacity limits at gyms, and reduced hours of operation at food and beverage serving establishments. The unemployment rate in the province rose 1.9 percentage points to 9.6%.

Newfoundland and Labrador, with reduced capacity at restaurants and fitness centres and the closure of bars, cinemas and performance spaces, saw employment fall by 3,900 (-1.7%) in January, after little change in December 2021. The decline was mainly in part-time work. The unemployment rate rose 0.9 percentage points to 12.8%.

Employment in Quebec fell by 63,000 (-1.4%) in January, the first notable loss since 12 months earlier, when the province was also under tight public health measures. In addition to capacity restrictions and closures at many service venues, the province was under a curfew instituted in late December 2021. Employment losses in January 2022 were mainly among youth aged 15 to 24 and men and women aged 25 to 54. The largest decreases were in accommodation and food services, with smaller losses in business, building and other support services and in professional, scientific and technical services. Meanwhile, more people worked in healthcare and social assistance. The unemployment rate increased 0.7 percentage points to 5.4%.

In the Montréal CMA, employment declined by 43,000 (-1.8%) in January, the first notable decrease since August 2021, and the unemployment rate rose to 5.8% (+0.8 percentage points). The unemployment rates in the CMAs of Sherbrooke (2.8%) and Québec (3.0%) were among the lowest in the country (three-month moving averages).

Following little change in the previous three months, employment in New Brunswick fell by 3,100 in January (-0.9%), while the unemployment rate was little changed at 8.5%. New Brunswick introduced capacity limits at restaurants, retail stores, malls and gyms at the end of December 2021 and closed dine-in service restaurants, entertainment centres, gyms and hair salons towards the end of the January 2022 LFS reference week.

In Saskatchewan, where indoor masking, proof of vaccination and physical distancing requirements were in place during the reference week, employment rose (+3,900; +0.7%) for the third consecutive month in January. The unemployment rate remained at 5.5%. Industries where employment has increased most notably in the past three months include business, building and other support services and construction. Employment in the Regina CMA was on par with January 2020, while in Saskatoon it was up 12,000 (+7.1%) compared with January 2020 (three-month moving averages).

Looking ahead: measuring quality of employment to build a fuller understanding of labour market conditions

The COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated that painting an accurate portrait of the labour market requires not only traditional indicators like employment and unemployment, but also measures of the quality of employment. Indicators of involuntary part-time work and low-wage employment, for example, have helped provide a deeper understanding of the impacts of each wave of pandemic-related employment loss and subsequent recovery. Record-high job vacancies have focused attention on the challenges facing employers seeking to recruit and retain workers, and the role that quality of employment may play in those challenges. These labour market indicators have been further complemented by insights from other sources, including social surveys on the mental health impacts of the pandemic and surveys of businesses concerning challenges resulting from supply chain disruption and the increasing cost of inputs.

To build on quality of employment indicators included in the main LFS questionnaire, Statistics Canada has enhanced the LFS program with a new series of supplementary surveys. Each month, respondents will be asked a short set of additional questions related to an aspect of quality of employment.

In January, respondents were asked whether they were planning to leave their current job, and whether quality of employment considerations were among the reasons for doing so. Fewer than 1 in 10 workers aged 15 to 69 (7.3%) were planning to leave their current job within the next 12 months, compared with 16.1% in 2016, when respondents to the General Social Survey were asked the same question (not seasonally adjusted). When January 2022 LFS respondents were asked to report their main reason for planning to leave their job, preliminary results show that at least 1 in 5 of those planning to leave (22.2%) reported reasons related to quality of employment, including low pay (15.7%), heavy workload (4.3%) and inability to do their current job from home (2.2%). A further 24.2% of workers cited a career change as the main reason for planning to leave their job (not seasonally adjusted).

Reflecting the fact that members of groups designated as visible minorities are more likely to work in lower-paid industries such as accommodation and food services and retail trade, visible minority Canadians (8.5%) were more likely than non-visible minority Canadians (6.7%) to report they were planning to leave their job in the next 12 months and to cite low pay as their main reason for doing so (23.8%, compared with 11.2%).

In the months ahead, Statistics Canada will continue to monitor different dimensions of the quality of employment and their impact on the well-being of Canadians. In February, new LFS questions will measure the willingness of Canadians to relocate to find a new job, while the March LFS will explore how workers evaluate career development opportunities offered by their current job.

Since the January LFS reference week, several provinces have made adjustments to public health measures, including a return to in-person schooling and the re-opening of indoor dining and recreation activities. LFS results for the week of February 13 to 19 will be released on March 11, 2022.

Sustainable Development Goals

On January 1, 2016, the world officially began implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development—the United Nations' transformative plan of action that addresses urgent global challenges over the next 15 years. The plan is based on 17 specific sustainable development goals.

The Labour Force Survey is an example of how Statistics Canada supports the reporting on the Global Goals for Sustainable Development. This release will be used in helping to measure the following goals:

Note to readers

The Labour Force Survey (LFS) estimates for January are for the week of January 9 to 15, 2022.

The LFS estimates are based on a sample and are therefore subject to sampling variability. As a result, monthly estimates will show more variability than trends observed over longer time periods. For more information, see "Interpreting Monthly Changes in Employment from the Labour Force Survey."

This analysis focuses on differences between estimates that are statistically significant at the 68% confidence level.

LFS estimates at the Canada level do not include the territories.

The LFS estimates are the first in a series of labour market indicators released by Statistics Canada, which includes indicators from programs such as the Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours (SEPH); Employment Insurance Statistics; and the Job Vacancy and Wage Survey. For more information on the conceptual differences between employment measures from the LFS and those from the SEPH, refer to section 8 of the Guide to the Labour Force Survey (71-543-G).

Since March 2020, all LFS face-to-face interviews have been replaced by telephone interviews conducted by interviewers working from their home to protect the health of both respondents and interviewers. While this has resulted in a decline in the LFS response rate, 45,000 interviews were completed in January and in-depth data quality evaluations conducted each month confirm that the LFS continues to produce an accurate portrait of Canada's labour market.

The suspension of face-to-face interviewing has had a larger impact on response rates in Nunavut than in other jurisdictions. Due to the larger decline in response rates for Nunavut, and resulting changes in the composition of the responding sample, data for Nunavut (table 14-10-0292-01) should be used with caution. To reduce the risks associated with declining data quality for Nunavut, users are advised to use 12-month averages (available upon request) rather than 3-month averages when possible. Statistics Canada will continue to monitor the quality of LFS data for Nunavut each month and provide users with updated guidelines as required.

The employment rate is the number of employed people as a percentage of the population aged 15 and older. The rate for a particular group (for example, youths aged 15 to 24) is the number employed in that group as a percentage of the population for that group.

The unemployment rate is the number of unemployed people as a percentage of the labour force (employed and unemployed).

The participation rate is the number of employed and unemployed people as a percentage of the population aged 15 and older.

Full-time employment consists of persons who usually work 30 hours or more per week at their main or only job.

Part-time employment consists of persons who usually work less than 30 hours per week at their main or only job.

Total hours worked refers to the number of hours actually worked at the main job by the respondent during the reference week, including paid and unpaid hours. These hours reflect temporary decreases or increases in work hours (for example, hours lost due to illness, vacation, holidays or weather; or more hours worked due to overtime).

In general, month-to-month or year-to-year changes in the number of people employed in an age group reflect the net effect of two factors: (1) the number of people who changed employment status between reference periods, and (2) the number of employed people who entered or left the age group (including through aging, death or migration) between reference periods.

Supplementary indicators used in the January 2022 analysis

Employed, worked zero hours includes employees and self-employed who were absent from work all week, but excludes people who have been away for reasons such as 'vacation,' 'maternity,' 'seasonal business,' and 'labour dispute.'

Employed, worked less than half of their usual hours includes both employees and self-employed, where only employees were asked to provide a reason for the absence. This excludes reasons for absence such as 'vacation,' 'labour dispute,' 'maternity,' 'holiday,' and 'weather.' Also excludes those who were away all week.

Not in labour force but wanted work includes persons who were neither employed, nor unemployed during the reference period and wanted work, but did not search for reasons such as 'waiting for recall (to former job),' 'waiting for replies from employers,' 'believes no work available (in area, or suited to skills),' 'long-term future start,' and 'other.'

Unemployed, job searchers were without work, but had looked for work in the past four weeks ending with the reference period and were available for work.

Unemployed, temporary layoff or future starts were on temporary layoff due to business conditions, with an expectation of recall, and were available for work; or were without work, but had a job to start within four weeks from the reference period and were available for work (don't need to have looked for work during the four weeks ending with the reference week).

Labour underutilization rate (specific definition to measure the COVID-19 impact) combines all those who were unemployed with those who were not in the labour force but wanted a job and did not look for one; as well as those who remained employed but lost all or the majority of their usual work hours for reasons likely related to COVID-19 as a proportion of the potential labour force.

Potential labour force (specific definition to measure the impact of COVID-19) includes people in the labour force (all employed and unemployed people), and people not in the labour force who wanted a job but didn't search for reasons such as 'waiting for recall (to former job),' 'waiting for replies from employers,' 'believes no work available (in area, or suited to skills),' 'long-term future start,' and 'other.'

Information on population groups

From July 2020 to December 2021, following the main LFS interview, respondents were asked a series of supplementary questions related to the labour market impacts of COVID-19. These supplementary questions included a question on membership in population groups designated as visible minorities. Beginning in January 2022, this question is included in the main LFS questionnaire and asked to all those aged 15 years and older. Due to this change, and associated adjustments to the weighting strategy, comparisons with data collected from July 2020 to December 2021 should be made with caution.

According to the Employment Equity Act, visible minorities are "persons, other than Aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour."

Possible responses to the question, which are the same as in the 2021 Census of Population, include: White, South Asian (e.g., East Indian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan), Chinese, Black, Filipino, Arab, Latin American, Southeast Asian (e.g., Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian, Thai), West Asian (e.g., Iranian, Afghan), Korean, Japanese, and Other.

Seasonal adjustment

Unless otherwise stated, this release presents seasonally adjusted estimates, which facilitate comparisons by removing the effects of seasonal variations. For more information on seasonal adjustment, see Seasonally adjusted data – Frequently asked questions.

The seasonally adjusted data for retail trade and wholesale trade industries presented here are not published in other public LFS tables. A seasonally adjusted series is published for the combined industry classification (wholesale and retail trade).

Next release

The next release of the LFS will be on March 11, 2022. February data will reflect labour market conditions during the week of February 13 to 19, 2022.

Products

More information about the concepts and use of the Labour Force Survey is available online in the Guide to the Labour Force Survey (71-543-G).

The product "Labour Force Survey in brief: Interactive app" (14200001) is also available. This interactive visualization application provides seasonally adjusted estimates by province, sex, age group and industry.

The product "Labour Market Indicators, by province and census metropolitan area, seasonally adjusted" (71-607-X) is also available. This interactive dashboard provides customizable access to key labour market indicators.

The product "Labour Market Indicators, by province, territory and economic region, unadjusted for seasonality" (71-607-X) is also available. This dynamic web application provides access to labour market indicators for Canada, province, territory and economic region.

The product Labour Force Survey: Public Use Microdata File (71M0001X) is also available. This public use microdata file contains non-aggregated data for a wide variety of variables collected from the Labour Force Survey. The data have been modified to ensure that no individual or business is directly or indirectly identified. This product is for users who prefer to do their own analysis by focusing on specific subgroups in the population or by cross-classifying variables that are not in our catalogued products.

Contact information

For more information, or to enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact us (toll-free 1-800-263-1136; 514-283-8300; infostats@statcan.gc.ca) or Media Relations (statcan.mediahotline-ligneinfomedias.statcan@statcan.gc.ca).

Report a problem on this page

Is something not working? Is there information outdated? Can't find what you're looking for?

Please contact us and let us know how we can help you.

Privacy notice

- Date modified:

Source: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220204/dq220204a-eng.htm

0 Response to "Have You Been Continuously Unemployed for the Last 27 Weeks Since at Least 08 16 2017"

Enregistrer un commentaire